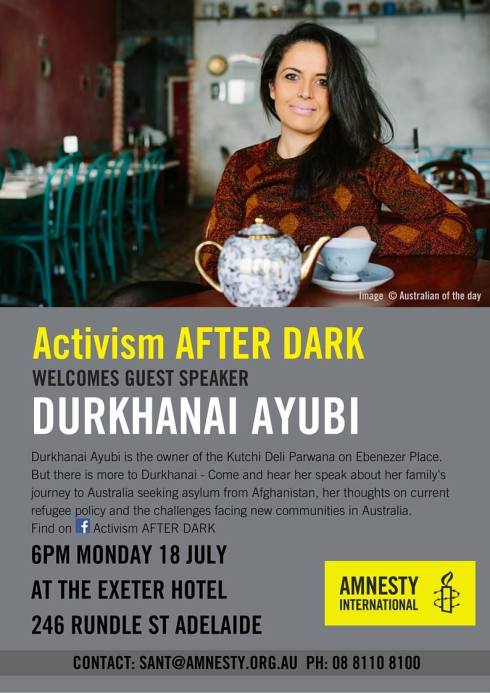

Last week I was invited as a speaker at an event hosted by Open Space Contemporary Arts. I was asked to speak about what kind of inequities we face as a nation, and what kind of future I imagined for Australia. I thought the brief was straight forward enough, until I really started to think about the root of our problems. I realised that to answer a question of how we might overcome inequities, I needed to ask a bigger question of how we justify it, and this, I think, is tied into an even bigger question – how do we view ourselves as a society and what is the narrative that binds us?

This was a bigger feat than I thought, because to try to unravel the steps that precede injustice, felt like following a trail of questions that lead deeper and deeper into the shadowy realm of what motivates human behaviour. It turns out, I think, that inequity today is largely justified by a collective mythology we all subscribe to in the West, without truly acknowledging the breadth and depth of its reach, which enshrines our own immediate desire, our ego, as deity.

So with that as a framework to understanding our challenges living in the 21st century Western world, I wanted to start with a relatively simple question – who are our heroes?

Below is a copy of my speech on the day.

Who are our heroes?

Every civilisation throughout history has its heroes – the beings which are held loftier than human beings. Who these heroes are, is based on that culture’s mythology – a powerful, and aspirational, story which shapes and defines those people. In our recent history, it was the universal religions of the monotheistic faiths that changed and shaped the world. Before that, in the ancient world, it was the heroes and deities of the polytheistic faiths who held man to account. And before that still, it was animism that set out the sustainable relationship between man and nature. Each has been an evolution of the system that preceded it, and has served humankind’s needs, as the world has grown increasingly complex and interconnected.

Despite their differences, and irrespective of whether we judge any of these systems as ‘right’ or ‘wrong’, all were doctrines which intended to serve a seemingly innate and continued human function: to create a framework that expected a certain standard of behaviour and which compelled individuals to live in the image of, and accountable to, something beyond themselves. But today, in the increasingly secular and ‘rationalised’ 21st century Western world, what is our mythology and who are our heroes?

In countries like Australia and all through the wealthy and developed Western world I would suggest that the biggest myth we subscribe to, is that we have no mythology. We increasingly view ourselves, or the best part of ourselves at least, as having risen above the ancient and improbable doctrines of creed. Whether this is true or not, is almost irrelevant. The question that is important for our future, that we must answer to ensure that we can negotiate the inequities and enormous challenges which face us as a global society, is, what now defines us and sets limits on our actions? What is the higher vision of ourselves?

I think we do have a mythology – one that can be followed as blindly and as fervently as any religion. And in that mythology – we are our own hero. The thing we worship and revere at the expense of almost everything else is ourselves, our ego. Our modern deities, then, the ones who we revere most, are the individuals with the most wealth and the most power. Capitalism, I think, is the creed we have developed with man at the helm, which validates ego as the ultimate master. By recognising our mythology and by thinking of our modern world in this way – a culture which values the centralisation of power and wealth – we can begin to explain why we value monoculture above diversity, why our democracy feels hollow, and why our notion of freedom is the strange bedfellow of destruction.

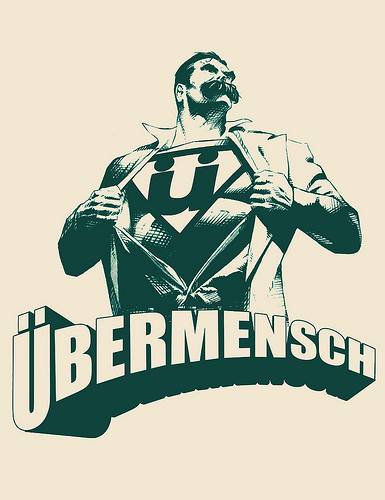

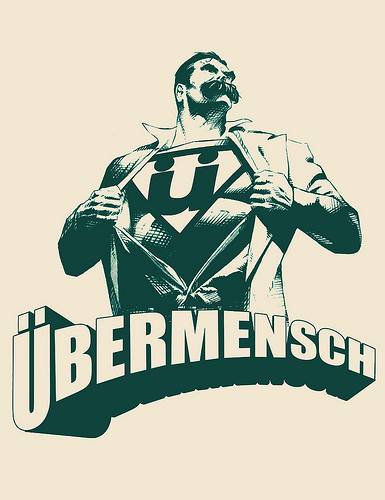

It was the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, in the mid to late 1800s, who predicted with astonishing accuracy the coming of a new mythology. He famously articulated this with the idea that “God is dead”. In his classic work of 1882, The Science of Joy, a central character, ‘the madman’ runs through the market place and cries out in frustrated realisation that “God is dead, and we have killed him, you and I!”. Nietzsche did not necessarily mean a literal death of God, but that, even within religious context, we were rationalising away the need for something beyond ourselves, or of being subordinate to another power or natural force. In another of his other classic texts, Thus spoke Zarathustra, the hero of the story, Zarathustra, comes to the realisation that all traditional sense of morality has died, and foresees the coming of the ‘ubermensch’ or the man above other men, the ‘overman’: “dead are all the Gods: now do we desire the overman to live”. This ‘overman’, Nietzsche suggests, will be his own hero, with a quest to function in a world where he or she is unaccountable to anything else.

It is no coincidence that Nietzsche predicted the rise of the ‘overman’ in an era where humanity was witnessing the birth pangs of industrialisation and capitalism in the Western world. This era has changed our landscape more rapidly in the space of a few decades, than evolution has over thousands of years.

This departure sets a new narrative for how we conduct ourselves in our world. I believe we are at a ‘critical juncture’ in our collective human story. When we have mastered our intelligence to the point that reliance on external forces has become disposable, we are left with little to hold sacred than ourselves.

Such a critical juncture in our collective thinking cannot take place without consequence. In my view, there are several areas where our modern mythology which glorifies ego as hero (lets call it the ‘ego-hero’), has profoundly impacted our vision of ourselves, and in turn, our world. By recognising the star role of the ego-hero in our mythology, we may be better able to comprehend the inequities of our society, and thus be in a position to affect change.

There may be many examples where we can apply the idea of the ego-hero in action, but I’ve chosen ones which I see as the most pressing, and which are perhaps most pertinent to me, in my experience as a migrant to Australia. I will go through them in turn, but they are:

- we have nothing to apologise for (our ego-hero is telling us we are beyond reproach and absolved of sin, including, and especially of, the original sin of European invasion)

- we have democracy (our ego-hero has convinced us to accept a version of democracy that surrenders power to our ‘deities’ – the most rich and powerful – without a real vehicle for influencing change)

- we are free (our ego-hero narrative tells us that the only freedom that counts is that of free markets)

*****************

Part 1 – We are beyond reproach

This belief is central to the core of our vision of ourselves. When the First Fleet arrived in Australia in 1788, with shiploads of European settlers, Australia’s first people were exposed to a harsh regime of racial oppression. The native population dropped by 90 percent. In Tasmania, the Indigenous population that had lived for over 10000 years in pure isolation, was wiped out by European colonisation almost down to the last man, woman and child, in the space of several years. Yet, we are rarely taught to accept this narrative as a part of our history. Our self-serving view of Australia as one of the most successful ‘multicultural melting pots’ in the world conveniently ignores that it was built on burning out large swathes of its original culture.

Our history largely is taught as beginning after European colonisation. There is a growing push to mute out this Indigenous history even further, with the Liberal Party instigating the review of the national curriculum out of the fear, to quote Christopher Pyne, that it has not properly “sold or talked about the benefits of Western civilisation.” Even more recently, Tony Abbott, when he was Prime Minister, argued that we could not continue to fund the ‘lifestyle choices’ of people in remote Indigenous communities, effectively arguing for another avenue to wipe out this culture even further by shutting down communities. In the same vein, now resigned, Liberal MP Dennis Jensen stated in February that the taxpayers of Australia can’t be expected to foot the bill for those who wish to live the lifestyle of the ‘noble savage’.

How have we managed to manipulate the reality of the violent eradication of Indigenous Australia into a narrative where Western values are actually the one under attack? This is a remarkable feat, only possible through the power of mythology. The one we have collectively subscribed to in the West – it tells us that monoculture is the best way. This subversive but pervasive reverence of monoculture, I think, comes from a deep seeded subconscious fear – one that challenges our ego-hero narrative.

The challenge is that different cultures have existed, and have existed powerfully and continually, throughout history, without a dependence on what our narrative has crowned as God – money and the ability to centralise power. This is why we can see those at the helm of our ego-driven mythology, our political class, let their real ambition occasionally slip out – create a nation where monoculture is valued and only money is important (hence the references to tax payer burdens at every turn). We do, however, occasionally pay lip service to diversity – with statements like, we’re a great multicultural society, or we have quotas for Indigenous people in our organisation. But the reality of action encouraged by the ego-hero is at complete odds with this idea of diversity.

Only those who conform to our broader myth get a ticket in, and those who don’t are punished. Look at what happened to Adam Goodes when he introduced a powerful idea of cultural diversity to the holy arena of AFL by celebrating a goal with an Indigenous war dance. He was brutalised because his action was a reminder to the rest of society that European settlement did try to reduce that power to nothingness. He was brutalised because it reminded us that perhaps there are sins that need absolving. He was brutalised because he challenged the ego-hero mythology we have enshrined as our religion.

Our tendency for war is justified, at least publicly, in a similar way. Our belief in the ego absolving us of all sin has managed to enable a narrative of using violence to liberate others. In reality, I think there are many layers beyond this publicly expressed sentiment, like imperialism and conquest of resources (all still related to the idea of ego-driven centralisation of power), but at least on a surface level, those we have empowered as our leaders have used our belief in ourselves above all else to effectively mobilise the narrative of the unapologetic hero to go to war – doing what it takes to protect our national interests and simultaneously achieving the noble feat of liberating others.

On the eve of invading Afghanistan, George Bush declared something to the affect of ‘today women are free’. There is even a George W Bush institute, which Lara Bush uses selflessly to help the women of Afghanistan, no doubt leading them to salvation. Similarly, Iraq and Syria have been invaded on the pretext of liberation.

The mythology of ego as our hero has allowed us to turn war into a favour.

Part 2 – We have real democracy

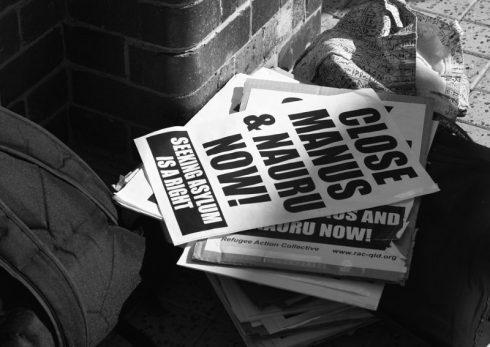

We have democracy in the West, but why is it that our democracy seems impotent? It is true that unlike many countries throughout the third world and the developing world, in the West, we do have freedom to identify with what we please, freedom to openly oppose establishments, freedom to ascribe to any religion, and freedom to vote for whoever we choose every three years without the threat of violence. So even though we have all this, why is it that when most of the population might be opposed to war, we still march into conflict? Why is it that even if a significant proportion of the population is against the dehumanising of people in detention centres, it is still the favoured method by both of our major political parties and takes place under a shroud of secrecy?

It’s because something precedes the values of democracy, and that is our even stronger belief in a system which worships ego. Our Western cultural mythology is embedded, before anything else, in the ethos of the individual and the ego. And as mentioned before, the wealthier and more powerful these individuals are, the greater our reverence to them. Why then, should we have any real expectation of this centralised power to hand itself over to meaningful democracy, which could only be truly spread by genuinely exercising the free and untainted will of people? When we have given the right signals to ego as our deity, we should not be surprised when the innately centralised nature of ego resists its own dilution, and does so effectively because we have empowered it to do so.

In her short essay but masterful essay, On the Abolition of all Political Parties, Simone Weil, a French philosopher of the mid 1900s, encapsulates an easy way for us to measure the validity of our democracy. She explains that the will of the majority – the underlying notion of democracy – is, in theory, good, because in taking a collective view on issues of importance, society is able to average out the sum of individual passions by neutralising the multitude of views until one prevails as justice and truth. However, and this is a big however, the collective will is only a valid indicator of truth and justice if in the expression of the peoples’ will, there are no external factors which induce a state of “collective passion”. Collective passion is a feeling of fervor that is spread by stoking things like fear and ego, and as Weil explains, is dangerous to democracy because it allows for entire countries to become unanimous in crime. Another requirement for democracy to function, according to Weil, is the ability for systems to incorporate the multitude of voices and views that it is built on to produce outcomes for the public.

I would say that our ego-hero culture creates a fertile breeding ground for the circumvention of true democracy. Firstly, collective passions are easily borne through an appeal to ego; think of the fear which is mobilised every time we are nearing an election. All of a sudden, refugees, the alien other, become an even bigger threat to our livelihood and advertisements appear on TV and on social media, telling us to be vigilant of terrorism and to be wary of our neighbour. It is possible then, that at present, the collective will of the nation is far away from truth and equity, implicating us all in crime.

Secondly, as mentioned earlier, the ego as our hero diminishes the importance of multiplicity and diversity, by believing in the centralisation of power. We expect that an all empowered singular voice will then perform the impossible feat of reflecting our diversity, asking for justice from within a two-party system which is inherently designed to make elected individuals conform to party politics. The core role for individuals in such systems then, is to work to win an election so that power can either be taken or continue uninterrupted, not to fight for diversity or for something as inconvenient to the ego as ‘truth and justice’.

Part 3 – We are free (our markets tell us so)

The idea of our freedom today is tied almost exclusively to our ability to consume, and very often at the expense of all other freedoms – like the freedom of people to live in peace, the freedom of other non-human inhabitants of our world, or the freedom of those in the developing world to be paid proportionately for their labour. The idea of wealth maximisation as a measure of the freedom of society comes from the capitalist ideology, so pervasive in our society now, that we don’t even think to question it. In 1776, Scottish economist Adam Smith published a landmark text The Wealth of the Nations. He made an argument in this text that creation of personal wealth and maximising profit is a moral good – because this private profit would then allow that individual to reinvest in society through employing others, for example. The more that wealth grew, the more people that private entrepreneur would be able to enrich. By deduction then, to follow ones selfish ambition for wealth acquisition, was actually, to be altruistic.

In essence, Smith’s text underpins every facet of our markets today – private profit above all else, and an unquestioning belief in free markets to settle inequity. But perhaps what was overlooked in this creed is the insatiability of the human desire for power – or the ego. Maybe Smith never imagined that this human propensity would create a situation where the first part of the equation was pursued aggressively – to maximise private profit, but not the second – to reinvest in society.

Perhaps in the 1700s it was beyond him to imagine that by 2016, 1 percent of the world would be wealthier than the other 99 percent combined, or that elaborate offshore tax havens and firms like Mossack Fonseca would exist, with a sole purpose to ensure the exact opposite of wealth distribution. Instead, we have a situation where, yes, the epic heroes of our time are becoming richer and even more untouchable in our narrative, but only at the expense of the rest of society. Billions of dollars annually of untaxed profits has been centralised into the hands of existing power, instead of distributed through the societies, whose people and natural resources were used to build that wealth, to eradicate poverty and invest in education.

Our current budget is built on this exact ethos – that reducing taxes for the richest and enabling them to increase their wealth and power is the best and most selfless thing for us all. Our government is using the mantra of ‘jobs and growth’ for us all, by reducing taxes and red tape for the rich, and a belief in the markets to redistribute wealth by subscribing to the idea that these benefits to those at the top will trickle down to the rest of us. But there is no evidence of this ever being the case, even in the United States, where heavy investment in such economic principles has taken place since the 70s. The only thing it will do is further ingrain inequality, as the wealthy hoard that wealth, not use it to stimulate the economy by providing ‘jobs and growth’.

Even the idea of posterity, of actions now aiding or hindering the quality of life of future generations, has been eradicated by the ego-hero. Every action – fiscal, social and political – is designed to satiate an immediate need, with little thought given to future implications. The driving impetus is to get rich quick, extract as much from the planet as possible now, and to devise policies which can meet the test of three year election cycle time frames, rather than to create strategies which withstand the test of time and act as an investment in future generations.

This inequity takes place because our mythology allows it to. So long as we see capitalism, the highest form of egoism, as altruism and something to be revered, we are investing in what the American spoken word poet of the 70s, Gil Scott Heron, called free-doom, not freedom. It is a system which is not exclusively confined to the realm of economics, but plays a prominent role in guiding the decisions of our political leadership, shaping our policies, and defining how we relate to one another.

Our unassailable belief in markets and wealth centralisation has allowed the devastation of the environment in the name of growth of the economy, and an open race in arms development, including nuclear proliferation. Our notion of individual freedom, our highest ideal, has lead to the two biggest threats to our very existence: environmental disaster, and the potential for nuclear war. Free-doom.

*****************

So we are not free and we know it. That uneasy feeling we get from time to time is perhaps our own imprisonment speaking to us. We feel it when markets collapse and cause global waves of inequity and unrest, when the cycles of nature become unrecognisable, and when we produce populist leaders that swell in significance proportionally to the hatred they espouse.

Inequities and injustices that take place at any given time can be best understood by studying the overarching mythology that dominates that society at any given time. The worst atrocities have always been justified by the highest principles set by society. God has always been used to justify brutalising the godless. And just so today, we are not unique. Our mythology embedded in the ego as a central doctrine, with maximisation of wealth and power as its central tenant, has justified brutalising the vulnerable – whether it be the poor and the voiceless, or the systems of nature that govern the planet.

At this moment in our nation’s story, we are part of a world which is more globalised and interconnected than ever – we are not an island. The threats that face us are global and have the potential to have global consequences. But likewise, the solutions to our greatest problems are universal also, and rely on the same human ingenuity that brought us to this point, to get us out. Perhaps no one individual has all the answers. But I think it begins by questioning – questioning the notion that we subscribe to no mythology, questioning the validity and usefulness of our ego-hero, and seeing ourselves within a broader story of the universe to understand our place.

Our doom is not inevitable, there are many possibilities before us yet to unfold. We may be a step closer to salvation by acknowledging two simple but potentially profound things. Firstly, by acknowledging that we are no different to the billions of people before us who have roamed the planet throughout the chapters of human existence. Just as they each invested themselves in a doctrine aspiring to something higher, we are too. Secondly, by understanding that maybe we have just chosen the wrong thing within this doctrine to revere. Perhaps we need to make sure that we glorify not our ego, which has crowned us self-made gods, but that truly godlike part of us that seeks to manage and contain it. Maybe then we can redefine our hero.

I am hoping that the ultimate cathartic experience in our hero’s journey is yet to come.

Tags: ego, freedom, freedoom, inequity, markets, overman, power